Religious Studies or Religious Education? A Personal Journey

Introduction[1]

Through a series of unexpected life turns, I completed two PhDs. Though I never had this as a life goal, I may be the only member of the LDS church who has a PhD in religious studies and another PhD in education.[2] These are the two primary disciplines that contribute to what is called Religious Education.

What follows is a bit of an autobiography, highlighting what I’ve learned in my journey in religious studies, and using my personal experience to explain my perspective on the similarities and distinct differences between religious studies and religious education.

Some years ago after having spent nearly a decade deeply immersed in the rigors of the discipline of religious studies, I found myself in a graduate school of education pursuing a PhD in instructional systems technology. I was bewildered.

In embarking upon this degree in education, I was once again in a university, much like I had been in university settings for more than a decade. But I was confronted with an entirely new value set, worldview, and set of perspectives, all of which I resisted for some time. I had spent more than a decade studying the arc of human culture, human thought, and human history in my biblical studies and religious studies programs. Wouldn’t the discipline of education simply find itself as a drop in the bucket in the larger perspective of the humanities? Could the discipline of education claim any truth, any reality, any rigor, any value? Could the field of education be trusted to have a viable perspective or useful insights? Would the field of education stand the test of scrutiny for being rigorous? For being dedicated to dispassionately seeking the best explanations for educational or learning phenomena? What could an academic discipline that got its start (if we are generous with dates) perhaps in the 1860s but more likely in the early 1900s, have to say about the great questions and needs in the world? Why didn’t my education classes turn to the historical past to takes its cues on truth, understanding, human nature, and learning? Why didn’t my education classes turn to the impressive swath of human philosophy, especially western philosophy that had been probing significant questions of human nature for seemingly as long as humans had pursued civilization?

I spent months in the academic field of education struggling in my mind with what I thought was inferior and useless thinking in the discipline, banal insights and philosophy, and untethered ideology. I thought that what I was experiencing in the field of education and learning was kindergarten thinking compared to the deep intellectual traditions I had experienced in my years in the discipline of religious studies.

Over time I was surprised to discover several things. First, I discovered that the field of education and learning are as rigorous and intellectually viable as the field of religious studies. Second, I discovered a deep level of hubris I had acquired because of my years in the culture of religious studies training. I erroneously assumed that scholarly integrity and rigor were the highest and only goods I could attain. I erroneously assumed that because I had studied human history through the discipline of religious studies that I understood better than anyone in the field of education why and how humans learn. I erroneously assumed that because I had studied the arc of human philosophy across the millennia that the field of education and learning would be a poor intellectual stepchild with “nothing new under the sun” to discover, teach, or share. I assumed that there was nothing inherent in the field of education and learning that was truly worth my while.

Because of my hubris, I was highly resistant to the field of education. I resisted its values. I resisted its discoveries. I resisted its discipline. I resisted its rigor. I resisted its usefulness and applicability. I wanted the field of education to conform to the world of the discipline of religious studies. And when it didn’t, I felt offended and bothered. I felt a need to protect the discipline of religious studies, to reassert the value and intellectual dominance of the discipline of religious studies. I believed that what learners needed was my discipline of biblical studies and religious studies. I had a hammer. Everything I saw was a nail.

I had to intellectually come to grips that the hammer I had may not be as powerful as I thought and that the world of problems often required many more and far more sophisticated tools than I had developed as a religious scholar. It was deeply humbling to discover that all the good I had experienced and encountered as I acquired the discipline of a religious scholar was, ultimately, insufficient to address the most pressing question for why I had joined that field: how can I help to transform lives? I had acquired an assumption that my discipline of religious studies all on its own had the power to empower positive change in lives, without the need for deep and serious input from—in fact, possibly with the direction and lead of—other disciplines. My mind struggled with that concept for a long time. I had to give up the myth that I sacrificed quality, or rigor, in scholarly thinking if I allowed other disciplines or other intellectual traditions into my scholarly life or even permitted them to take the lead. Only by being a disciple, or advocate, for learners to have their lives expanded could I shed the shackles of being required to be loyal exclusively to any single discipline. I could seek after truth wherever it may be found and use the best truths, whether I developed them, or borrowed them, whether they came from my first love discipline of religious studies or not. I could be liberated to find and apply truth instead of being required to use only the tool set called religious studies.

I was a slow learner, because of my hubris and because of my myopic way of believing that I had to be loyal to the discipline of religious studies at the expense of all other forms of truth, knowing, and doing. I didn’t realize at the time that I was making these decisions, that I was acting on hubris. I didn’t realize what I was resisting. With no further thought or questioning, I had erroneously assumed that my first chosen discipline of religious studies held the keys of epistemology, ontology, meaning making, and truth living. But what else could I think? I had adopted the unspoken academic standard to be intellectually monogamous. Once I had married the field of religious studies, there could be no other truth to catch my eye, no other discipline to capture my fancy, no other epistemological worldview to hold my heart. I had been disciplined to believe that there was no other way to see the world that could bring value. I feared that to take the discipline of education seriously and on its own terms, I’d be unfaithful to my first love, religious studies. I began to suffer cognitive dissonance. Was it truly possible to love, embrace, and apply two entirely disparate intellectual traditions and disciplines that have very few areas of clear overlap?

What would I lose if I took the discipline of education seriously? What would I lose if I discovered that education had something to teach me as a religious studies scholar that I had not experienced or encountered in the discipline of religious studies? Could the field of education have anything of value to teach religious studies? What, really, did the discipline of education and learning have to say about religious studies, about the human condition, about why religions grow and evolve, about why people are (or are not) religious, about the power of religion to shape human history? Wouldn’t I have to abandon the rigors, the values, the strengths, and the insights of religious studies to embrace the discipline of education and learning? Could I really have two masters? Could I be intellectually polyamorous, or did careers in higher education require intellectual monogamy with the first commandment being “thou shalt have no other disciplines before you”?

Perhaps I’m overstating my case to say I acted on hubris. Perhaps the better word is ignorance. For all that I had learned and experienced in my life, I had limited or no experience with other disciplines that had incredibly rigorous and sophisticated tools for helping to transform lives. Life transformation is another way of naming “learning.” So maybe it wasn’t hubris. Maybe it was lack of experience. Whatever I call it, this lack blinded me or created obstacles for me for some time from finding and using all the tools to meet my dream to help others have improved lives.

Of course, to summarize several years of intellectual agonizing into a few short paragraphs does not do full justice to the experience. But this description hopefully gives a taste of the intellectual and epistemological struggles I endured as I pursued two PhD programs simultaneously, and the two intellectual traditions of these PhD programs were as different as a fish and bicycle. Over time, I learned that I could love both equally for what they were and that bound together they could be more powerful and useful.

I now see the discipline of religious education as combining these two disciplines. In fact, I see religious education as subsuming religious studies. In my estimation, religious studies typically excludes religious education while religious education embraces religious studies. How and why?

My definition of religious studies is the scientific study of religious phenomena.[3]

My definition of religious education is the disciplined pursuit and application of truths to empower life-long learners.[4]

Religious education and religious studies have distinct purposes. Religious studies exists to scientifically study religious phenomena, to document those discoveries, to have those discoveries competently reviewed and verified by a peer (another scientist of religion) and then to have those discoveries published and deposited in journals and libraries that are typically only available to other scholars.

Religious education exists to empower learners to be more than they were when they began the religious education experience, specifically to learn and apply saving truths as found in revelation ancient and modern.

Religious education rigorously seeks to develop learners through the means of religious principles and history, and extraordinary teaching and learning experiences. The culture of religious studies is not focused on the development or learning or becoming of individuals. Religious studies is focused on rigorously studying religion. Religious education, on the other hand, combines the rigorously developed knowledge from religious studies with the science of learning to develop learners who embrace their religion. Studying religion is the end or purpose of religious studies. The purpose of religious education is to help individuals become their best selves by living their religion. On its own, religious studies is neither necessary or sufficient to create lives of becoming. Religious education, when it seriously takes advantage of the best of the learning sciences, is well positioned to help learners know, embrace, and live their religion.

My perspective is that what I’ve shared is not common knowledge in religious studies. My observation has been that, in general, the scientific disciplines that inform teaching and learning are generally ignored in the pursuit of religious studies. Why? Because typically, as is the case generally in higher education, scholars borrow from other disciplines when it informs their scholarship, but not to inform teaching and learning. Scholars typically derive insights about teaching and learning from others in their discipline. We trust our tribes more than outsiders. Consider this: Scholars of religion typically find it untenable that people get their opinions about religious phenomena from uninformed voices who have not been trained in the science of studying religious phenomena. Yet that same principle is not often applied to teaching and learning practices in religious studies. Scholars of religion usually turn to their own peers and colleagues to inform how to design learning, instead of turning to experts in the field of learning design.

To demonstrate this, let me share more about the cultural conflict I experienced in pursuing two PhDs simultaneously. Over time I became more acculturated and attuned to incongruous statements made by academics about teaching and learning. I heard other scholars promote, speak of, and seek to enact higher education cultural myths, which upon further inquiry actually represent educational malpractice, but were left unchecked. I’d spend the morning engaged in the discipline of rigorously designing and testing learning systems. Then in the afternoon, I’d participate in my religious studies courses. Seldom in these courses were there discussions of what it means to be a teacher, how to teach, how to rigorously assess learning needs among learners, how to rigorously design learning, or how to rigorously evaluate learning. Even though most of us PhD students were hoping to become religious studies professors, for whom teaching would be a key activity, when we talked about teaching and learning, our conversations were not informed by the science or discipline of education but rather the myths of higher education. What did I hear instead? Professors and graduate students spreading opinions about what education is, what learning is, and how it should take place. Never were any of their statements grounded in rigorous educational philosophy, research, evaluation, assessment, data, or evidence. It was simply the traditions of the academic fathers handed down over the generations from teacher to student to be replicated across universities everywhere without question.

I was stunned. Here I was in one of the finest religious studies graduate programs in the nation where every religious studies claim was poked and prodded. Every claim was held up to scrutiny. Ever claim demanded verifiable evidence. No one in my observation of the religious studies program, neither the professors nor the students, would take someone’s religious studies opinion at face value without questioning the sources of evidence and methodologies for interpreting the evidence. Then on the other hand, no one in my observation demonstrated any self-awareness that their claims about teaching, learning, and education were not based in empirical, rigorous evidence. In a graduate religious studies seminar where the question of learning how to teach came up, one of the professors said with confidence and total sincerity, and without shame or any sense of self-awareness of the incongruity of what he was saying as a teacher, “Look, I’m not paid to teach. I’m paid to research.” This one statement sums of the pervasive culture of values that inhabit the discipline of religious studies and PhD-level academics in general.

To get a PhD means to be trained how to research rigorously your chosen discipline. Yet the truth is that to obtain a PhD is insufficient to be qualified to teach. One of the enduring myths of higher education is that the more you know, the better the teacher you are. All of us have had experience with seemingly brilliant professors who couldn’t teach. The discipline of teaching and learning is as sophisticated and as complex as any discipline in higher education. In fact, I call the disciplines of education, learning, and teaching “hard sciences” because they deal with humans. Humans are far more difficult to study and quantify than any other natural phenomena, in my opinion. So, if teaching and learning is such a deep, sophisticated, and complex subject, why would we believe that simply knowing a lot about a topic matter qualifies us to teach? Because for centuries the system of higher education has had as its most important qualification to become a professor the holding of the PhD degree.

If learning to rigorously research a topic takes years of guided practice and experience, wouldn’t learning how to design sustainable and life-changing learning experiences for learners require the same PhD level of intense effort? Our current higher educational system doesn’t require that type effort for people with PhDs before they are put in the classroom (or even after they have been in the classroom for any amount of time). We assume that anyone with a PhD can stand and deliver. Talking, so goes the higher education myth, is teaching. For anyone who has even a limited experience in the discipline of teaching and learning, as a rigorous intellectual system, the traditional belief that someone who knows a lot would make a great teacher is as wildly fallacious and unsupportable as is the statement that a recently returned missionary is a scripture scholar. Religious studies and scripture scholars immediately recognize that a recently returned missionary, despite any facility with the scriptures, is a long way from being a bona fide scripture scholar. That is obvious to religious studies and scriptural experts. What should be obvious as well is that simply knowing a lot, as recognized by the attainment of a PhD, is not sufficient to being a transformative teacher or learning designer. Except for those deeply versed in the intellectual discipline and practices of teaching and learning, too few in higher education understand this.

As I gained more experience in the discipline of education, my awareness of cultural myths permeating Higher Education grew and became more refined. I came to be very suspicious about the ability of religious studies, as a discipline, to say anything of value about how people learn or how to teach. The discipline typically did not ask or answer such questions and the discipline certainly does not have the rigorous tools designed or developed to address such questions. That was a disturbing and disappointing discovery. Why? I had joined the discipline of religious studies more than a decade before with the intent that I could better master religious thinking and scripture to better help people find greater peace, joy, and happiness. What did I eventually learn? That religious studies, all on its own, does not have the tools, rigor, discipline, values, skills, or mindset to change learners’ lives. We need a multi-disciplinary, interdisciplinary approach.

One of my experiences on this road of unexpected discovery happened during my first semester of my double PhD program. I created a readings course under the direction of a professor from my education program with added direction from a professor in my religious studies/biblical studies program. The question I pursued was “What is the theory and science of learning and teaching in the discipline of religious or biblical studies?” That question seemed compelling for me to pursue for several reasons. First, the most likely job I’d have in the future would be as a religious studies scholar who studied and taught religious studies. I wanted to better understand the theories and practices of teaching and learning that religious studies scholars had developed. Second, since I was pursuing two PhDs at the same time (in religion and in education), it seemed obvious that I should immediately tackle a question where these two disciplines had overlap. Surprisingly, I was confused for most of that semester. I read, and read, and read searching for meaningful discussion on the topic. I talked to lots of people. I drove to Wabash College, which has an internationally recognized center dedicated to the scholarship of teaching and learning in theology and religious studies. I interviewed the Wabash Center directors and browsed their impressive library.

What did I discover after a semester of work? First, the discipline of religious studies has only recently discovered that there are entire scientific disciplines (that is, they are not informed by religious traditions) devoted to studying teaching and learning. Second, the discipline of religious studies has no coherent theory, practices, or science for teaching and learning. Much was done by convention, by hearsay, by tradition. Worse, the little educational theory and science that was going on in these publications was grounded in religious studies research, reasoning, and philosophy and not in educational research or practice.

For example, I’ve seen scholars of religion try to design learning experiences that are based on the philosophies they’ve adopted in religious studies programs such as post-modernism or Marxism. Have any of these scholars asked if reputable education scholars use any of these ideological perspectives to design learning? Have they reviewed any serious, scientific research about whether such approaches are tenable for accomplishing the core purposes of religious studies programs? Or, I fear, are such scholars practicing a form of ideological imposition upon the students without the students’ consent? I’ve seen such practices among some scholars of religion and I’m left wondering at the ethics of such uninformed choices.

Another example of religious studies speaking about education untethered from the disciplinary perspectives of education was hammered home to me by a book I read (which I long ago misplaced and have not found again, to my chagrin). This book was written by leading biblical scholars dedicated to the topic of how to teach. I was surprised to see that instead of talking about how to rigorously understand learners and to design learning based on what learners need, there were long conversations about what to teach. How do I know what to teach if I don’t first know what my learners need? How can I know what my learners need if I do not know my learners? If I haven’t asked them?

I was really disappointed. The discipline that had nurtured me for so long had demonstrated a glaring lack of understanding, unaware that the question of what to teach is typically the last question that should be answered when designing learning for learners. Answering the question what to teach is the tail wagging the dog, the cart before horse, the answer before the question. We had substituted the means with the ends. The purpose I saw demonstrated in religious studies scholarship was to demonstrate rigorously tested knowledge about religious studies, not the positive development of learners’ lives. Yes, I knew, rigorously tested truth was required to help people’s lives be transformed. But that is not what I discovered in my studies of religious studies. I had expected better of my discipline of religious studies. Only upon reflection did I realize, “Why would I expect that those of us in religious studies would have evolved, empirically grounded, and sophisticated theories and practices of teaching and learning when the what of our discipline is focused on religious phenomena, not on teaching religious phenomena or helping others to learn and apply the truths of religious phenomena?”

I learned that my first love, religious studies, was not equipped to address the question, let alone apply the answer, “How do learners learn?” Wasn’t that the point of science and higher education in the first place? To discover as much truth as possible and then to help as many people as possible experience and apply those truths?

With this realization, myths that I had embraced were shattered, including my assumption that religious studies is the most intellectually vibrant and rigorous discipline.

Questions I’m Still Grappling with in Religious Education.

- If the purpose of religious education is to build and fortify faith in Jesus Christ, what is the purpose of religious studies?

- What problem(s) does religious studies solve? What needs does it address?

- What role should religious studies play in my work and career in religious education?

- Can I as a religious educator really do my best work with learners if most of my time is focused on more content acquisition for myself?

- If I have to be trained in biblical languages in order to more responsibly interpret the biblical text, shouldn’t I also be trained in assessment design, assessment delivery, and assessment interpretation before I can competently assess learners in my charge?

- If I’m trying to transform lives, does the culture, attitudes, skills, and knowledge found in religious studies have all, or even the best, of what I need to help learners?

- Am I informing learners (forming them in the image of my discipline) or educating them (leading them out from wherever they are to a new place of becoming)?

- Who am I most loyal to: My discipline, my peers, or my learners?

- Is knowing religious studies the same as being able to teach religious studies? Or to teach religious education? Or to help learners grow in the purposes of religious education?

- Is teaching best done by those who know the most and can share that knowledge with others or by those who are expert learning designers or some combination of the two?

- Is there a difference between teaching and learning?

- Can a teacher exist without learners? How does our answer to this question change the way we think of teaching and learning?

- Can learners exist without teachers? How does our answer to this question change the way we think of teaching and learning?

- Do I as a scholar in the discipline of religious studies spend as much time studying and applying the science of teaching and learning as I do the scholarship from the discipline of religious studies?

- Do I as a scholar practice the discipline of learning design as rigorously as I practice the discipline of research?

- As a scholar in the discipline of religious studies, do I experiment as rigorously on my own teaching as I do on my research questions in religious studies?

- As a scholar in the discipline of religious studies, do I experiment as rigorously on my learners’ learning as I do on my research questions in religious studies?

- As a scholar in the discipline of religious studies, have I sought to be as competent in learning design as I am in research design?

- As a scholar in the discipline of religious studies, do I seek first to understand my learners’ learning needs and goals before I design what or even how to teach?

- As a scholar in the discipline of religious studies, am I more interested in first rigorously professing the discipline before I know what the learners need?

- As a scholar in the discipline of religious studies, do I take my cues on what and how to teach from peers in religious studies, or from experts in the scientific disciplines of cognitive development, teaching, design, and learning, and related fields?

- As a scholar in the discipline of religious studies do I rely on my gut or on what I have seen other religious studies scholars do? Or do I rely on scientifically verified approaches to determine how to teach or how to help learners learn?

- As a scholar in the discipline of religious studies, do I rely on how I was taught to teach?

- Which is more important, teaching or learning?

- Which is more important, that the teacher learn more or that the learner learn more?

- In religious education, who is my primary audience?

- In religious studies, who is my primary audience?

- In religious education, what am I producing?

- In religious studies, what am I producing?

- At BYU, and in the Church Educational System generally, which culture should predominate, religious studies or religious education? Which culture could we do without?

Seriously answering these questions should highlight that the discipline of teaching and learning is intensive and extensive, and that the culture of religious studies is quite different from the culture of teaching and learning (which I think is better represented by religious education). To truly engage in the rigors of becoming a better teacher and learner takes serious time, effort, and thought. This is just like the field of religious studies. To push forward the boundaries of understanding religious phenomena requires significant focus, effort, time, and thought. We need such effort. Without better truths, what would teachers teach? If I’m a competent teacher and I design the most fabulous learning experiences for learners but I have inferior truths or insights packed into the learning experience, well, that is a disaster. Strong religious studies scholarship is needed and wanted. In our drive to improve teaching and learning, we must make use of the best in religious studies scholarship. But as religious studies scholars, we should be deeply humble and introspective about whether our skill sets as scholars of religion are appropriate and sufficient to design learning experiences for what our learners most need. What we are likely to find is that we need the rigors of other disciplines to help us accomplish our goal to empower learners’ lives, which is the purpose of religious education.

The Elephant in The Academy

The real question to address for the future of religious education at BYU (and for the future of CES in general) is this: Which culture or model should be predominate as the guiding force for religious education?

Since religious studies does not have a lock on quality or rigor, religious studies does not have any special claim on religious education, except, perhaps in some of its content mastery. Even so, mastering religious studies is not the same as mastering the gospel. Furthermore, content mastery is not the purpose of religious education. Rather, learning and doing the gospel is the purpose of religious education, not simply learning about religion and history. Content mastery is necessary, but insufficient.

Therefore, caution and suspicion should be exercised when the culture of religious studies seeks to exert its influence in religious education beyond urging the rigors of content mastery. If the dominant filters, through which all activities and goals in religious education are measured, are rigor, quality content, or content mastery, ultimately the learners will lose if we forego the rigors of learning design, experience, and assessment.

The purpose, promises, and future of BYU generally and religious education specifically will be comprised if religious studies becomes the dominant voice. For religious education to achieve its mission, it must employ the concepts, values, and voices of a multitude of disciplines that all have at their center the learner. Since religious studies has evolved over time with the scholar at the center of its values and cultures, religious studies, as its culture is currently positioned, is antithetical to the culture of putting the learner and the doer—not the scholar, not the teacher, not the academic—at the center. Because the paradigm of religious studies is focused on “knowing” about religion, what often is missed is the “being” and “doing” of religion. Religious education is focused on living and doing religion. Again, someone who has exclusive training in religious studies may be adept at delivering content (even rigorous content), but they may not have rigorous training in how to create learning experiences for learners to do religion. That is, simply knowing about religion does not necessarily lead to actually living or doing religion. The doing and living of religion is, in my perspective, one of the major purposes of BYU generally and religious education specifically.

We should therefore have a healthy level of skepticism for any voice that claims to know how and what we should teach learners, if that voice has never been trained in the rigors of learning design, user experience design, assessment and evaluation, or the various related fields whose scientific focus is how to design, deliver, and measure extraordinary experiences.

I realize that what I’m saying may concern some. The immediate criticism may fall into these categories:

- If we put learners at the center, critical thinking will be compromised.

- If we put learners at the center, rigor will be compromised.

- If we put learners at the center, quality will be compromised.

- If we put learners at the center, content will be compromised.

- If we put learners at the center, then we’ll lose control as scholars.

- If we put learners at the center, then amateurs instead of experts are leading the way.

These, and similar concerns, are all understandable. Quality, rigor, and critical thinking are not the sole domain of those trained in religious studies and related disciplines. Every scholarly, scientific, and academic discipline aspires to achieve, and works to demonstrate, quality, rigor, and critical thinking. So concerns #1, #2, and #3 can be dismissed. Concerns #4, #5, and #6 are also empty concerns. When learners are put at the center, content becomes the means and not the end. One of the problems of the culture of higher education is that the content is the means and the ends. We silo ourselves into disciplines that are taught by individuals who have exclusive loyalty to the discipline and in some cases near exclusive experience in only one discipline or methodology. By that long experience of disciplined culture, we may come to believe that our discipline holds the keys of life transformation for our learners and we believe that that transformation will occur via the content that we have mastered. We hold the belief (based on personal experience and the corroborating anecdotal stories we hear from those in our peer group who have been trained just like us), without longitudinal evidence, let alone scientific evidence, that the content of our discipline holds the secrets to ennobled lives.

If we instead practice critical thinking, challenging our own received traditions, we may discover that the discipline we’ve devoted our lives to may be insufficient to accomplish the goal of enhancing learners’ lives. If we respond that our job is to push forward the boundaries of our discipline, to pursue rigorous research, then we have a slightly different conversation to consider, because this response demonstrates that the scholar is first and foremost loyal to their discipline, to their similarly trained scholarly peers, and to their content rather than being first loyal to learners and learning.

If we are more loyal to our disciplines than we are to our learners, we are like the proverbial sales person who is more interested in convincing someone to buy what they have, rather than listening to what the buyer needs and giving the buyer the tools, abilities, and learning necessary to find what they really need. And that solution may be different than what the sales person has to offer.

The scholar who is first and foremost loyal to his learners will, of necessity, need rigorous, high quality truth to do his job, but only after he has discovered his learners’ learning needs and designed and implemented appropriate solutions and experiences to meet those needs.

Conclusion

We need the rigor of religious studies to guide us to the best ideas for understanding religious phenomena. And we need religious education to help learners have the most appropriately designed learning experiences possible that leads to living religion, and not simply thinking about religion.

Truth, or great conceptual ideas, are insufficient to create robust learning experiences. We must pair the most robust learning design principles and practices with the most robust knowledge we have from the field of religious studies. That pairing creates religious education. And religious education exists first and foremost to focus on the transformation of the learner, especially as a disciple of Jesus Christ.

Religious education should be the dominant, leading paradigm and value-set for CES. Religious studies should only play a supporting role. The culture and values of religious studies should never lead out or guide in religious education or CES. Any efforts to do so should be met with firm but kind and informed resistance. Instead, the values and purposes of religious education should lead out in seeking to transforms the lives of students within the Church Educational System, including and especially at BYU Provo.

Suggested Readings for Religious Studies vs Religious Education (arranged chronologically)

Joshua Eyler, How Humans Learn: The Science and Stories Behind Effective College Teaching (Morgantown, WV: University of West Virginia Press), 2018.

John Couch and Jason Towne, forward by Steve Wozniak, Rewiring Education: How Technology Can Unlock Every Student’s Potential (BenBella Books, 2018).

Sam Wineburg, Why Learn History (When It’s Already On Your Phone)? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

Elizabeth Green, Building a Better Teacher: How Teaching Works (and How to Teach It to Everyone) (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2015).

Julie Dirksen, Design for How People Learn (2nd edition) (San Francisco: New Riders, 2015).

Saundra Yancy McGuire, Teach Students How to Learn: Strategies You Can Incorporate into Any Course to Improve Student Metacognition, Study Skills, and Motivation (Sterling, VA: Stylus, 2015).

Peter Brown, Henry Roediger III, and Mark McDaniel, Make it Stick: The Science of Successful Learning (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2014).

Carl Olson, The Allure of Decadent Thinking: Religious Studies and the Challenge of Postmodernism (1st Edition) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Wilbert J. McKeachie, Teaching Tips: Strategies, Research, and Theory for College and University Teachers (14th Edition) (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing, 2013).

Jared Stein and Charles Graham, Essentials for Blended Learning: A Standards-Based Guide (New York: Routledge, 2013).

Arthur Levin and Diane Dean, Generation on a Tightrope: A Portrait of Today’s College Student (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2012).

David J.A. Clines, “Learning, Teaching, and Researching Biblical Studies, Today and Tomorrow,” Journal of Biblical Literature 129, no. 1 (2010), 5-29, https://www.sbl-site.org/assets/pdfs/presidentialaddresses/JBL129_1_1Clines2009.pdf

Trudy Banta, Elizabeth Jones, and Karen Black, Designing Effective Assessment: Principles and Profiles of Good Practice (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010).

Craig Nelson, “Dysfunctional Illusions of Rigor: Lessons from the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning” in L. B. Nilson and J.E. Miller (Eds.) To Improve the Academy: Resources for Faculty, Instructional, and Organizational Development, no. 28 (2010), 177-192, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/j.2334-4822.2010.tb00602.x

Barbara Gross Davis, Tools for Teaching (2nd Edition) (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2009).

John Medina, Brain Rules: 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and School (Seattle, WA: Pear Press, 2008).

Harry Lewis, Excellence Without a Soul: How a Great University Forgot Education (New York: PublicAffairs, 2007).

Marcy P. Driscoll, Psychology of Learning for Instruction (3rd Edition) (Boston: Pearson, 2005).

Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe, Understanding by Design (Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2005).

Ken Bain, What the Best College Teachers Do (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004).

John Tagg, The Learning Paradigm College (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003).

Eleanor Boyle and Harley Rothstein, Essentials of College and University Teaching: A Practical Guide (Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press, 2003).

James E. Zull, The Art of Changing the Brain: Enriching the Practice of Teaching by Exploring the Biology of Learning (Sterling, VA: Stylus 2002).

Sam Wineburg, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001).

Lorin W. Anderson and others, A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Abridged Edition 1st Edition) (New York: Pearson, 2000).

Robert Barr and John Tagg, “From Teaching to Learning: A New Paradigm for Undergraduate Education” Change (November/December 1995), https://www.colorado.edu/ftep/sites/default/files/attached-files/barrandtaggfromteachingtolearning.pdf

Arthur Chickering and Zelda Gamson, “Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education” Washington Center News, (Fall 1987), http://www.lonestar.edu/multimedia/sevenprinciples.pdf.

FOOTNOTES

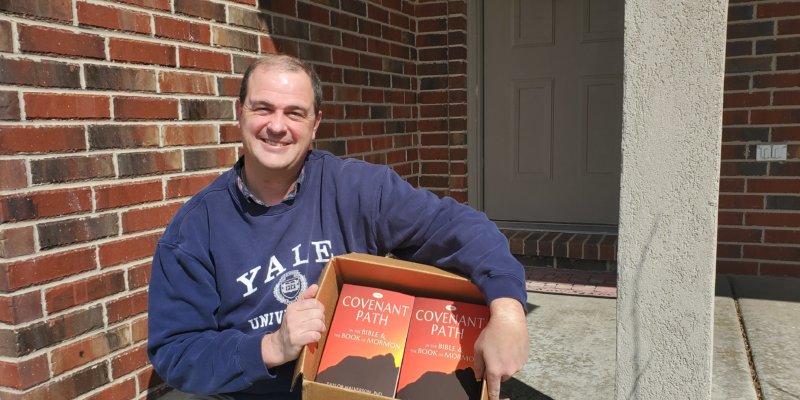

[1] Taylor Halverson is an Entrepreneurship Professor in the BYU Marriott School of Business and formerly a Teaching and Learning Consultant at the BYU Center for Teaching and Learning. He has a PhD in Judaism and Christianity in Antiquity (from the Religious Studies program at Indiana University) and a PhD in Instructional Systems Technology (from the School of Education at Indiana University). This article was originally composed in 2018. Given the recent direction from the BYU Board of Trustees and the Brethren on the purposes of Religious Education at BYU, it seemed appropriate to release this article to the public.

[2] For those interested in my Religious Studies background, my PhD advisors in Biblical Studies (the official title of the program was “Judaism and Christianity in Antiquity”) at Indiana University were Dr. Steven Weitzman, Dr. David Brakke, and Dr. J. Albert Harrill. Dr. Weitzman completed his PhD at Harvard University in Ancient Near Eastern and Biblical Studies under the direction of Dr. James Kugel (of Harvard University). Since Indiana University, Dr. Weitzman has had professional appointments in Biblical Studies at Stanford University and the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Brakke completed his M.Div degree in Biblical Studies at Harvard University and his PhD in New Testament Studies (Religious Studies) at Yale University under the tutelage of Dr. Bentley Layton (of Yale University). Since Indiana University, Dr. Brakke is now professor of History at the Ohio State University. Dr. J. Albert Harrill completed his PhD at the University of Chicago in New Testament Studies (Religious Studies) under the direction of Hans Dieter Betz (of the University of Chicago). After his time at Indiana University, Dr. Harrill is now professor of Classics at the Ohio State University.

[3] I recognize that there are a variety of definitions constituting what is religious studies. These definitions all essentially boil down to the academic enterprise of seeking to understand and interpret religion (however one might define religion, which itself can be a squishy concept).

[4] I recognize that my definition of religious education is slightly different than that published by the BYU College of Religious Education, which is much more focused on what professors do rather than on what the learners will do and become: “The mission of Religious Education at Brigham Young University is to assist individuals in their efforts to come unto Christ by teaching the scriptures, doctrine, and history of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ through classroom instruction, gospel scholarship, and outreach to the larger community.” Accessed at https://catalog.byu.edu/religious-education on 7/16/2019.